Author(s): Bharat Lal Seth

Issue: Dec 31, 2011 Asian Development Bank’s new plan insists on the private sector answer to water woes

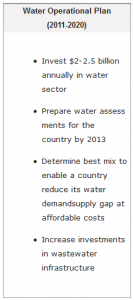

TAKING stock of its water operations, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has set guidelines for an investment of US $2-2.5 billion annually in the water sector for the next 10 years. The guidelines, called Water Operation Plan, however, do not define the exact approach to water operations.

Critics say the plan gives countries the option to seek financial help and expertise from the private sector on water projects. This facilitates and encourages governments like India to allow private investments to address the issue of water scarcity and find markets for companies based in donor countries.

The first-of-its-kind guidelines, approved in October, are based on the understanding that water has an economic value. “These guidelines prove that ADB’s plans have been unsuccessful until now due to public opposition to water service charges,” says Hemantha Withanage, executive director of Centre for Environmental Justice, a non-profit in Sri Lanka. An ADB evaluation of its water projects in 2008 found that attempts at tariff reform, achieving cost recovery in services, initiating regulatory reforms and involving the private sector remained “intractable”. Another assessment in 2010 found that nearly half of the projects failed to meet targets like increased tariff and cost recovery.

The guidelines make clear that countries cannot risk waiting for investments, and can seek to advocate projects involving investment and expertise from the private sector. “They are attempting to commodify water in Asia,” says Withanage.

ADB has for long held that limited participation of the private sector in water services is a cause for concern because of the limitations of the public sector to expand investments. The drive to foster a culture of payment for water as a service has suffered from a general unwillingness to charge. Providers therefore remain short of capital. “The public and private both have failed,” says Avilash Roul, executive director of NGO Forum on ADB, a network of 250 non-profits formed to make ADB accountable to the impacts of its projects. The governments cannot outsource their responsibility to provide basic services to the people. Private players can at best invest their money for such activities which must be controlled, managed and owned by the public sector enterprises, adds Roul.

Through the guidelines, ADB intends to make the relationship between water, food and energy stronger. “Many Asian countries are experiencing chronic water shortages. Since nearly 80 per cent of the region’s water is used in agricultural production, water shortages can contribute to shortages of food,” says Alan Baird, senior water supply and sanitation specialist with ADB.

Combined with energy insecurity, the increasing shortages in water and food may reverse Asia’s hard-won gains in poverty reduction, he adds. Therefore ADB is committed to funding hydropower development. “Integrated water resources management has transformed into this so-called nexus which ADB adopted last year. This points to how smoothly ADB policies can morph, for instance, to support hydropower structures in the eastern Himalayan rivers,” says Roul.

According to ADB, the water-food-energy “nexus” is critical in achieving equitable water security across Asia. “It is not an exercise to promulgate dam building,” says Baird. ADB works with a broad range of stakeholders. In 2010, 80 per cent of loans, grants, and related project preparatory technical assistance approved included some form of participation from civil society organisations, says Baird. “Despite ADB’s proclamation of a multi-stakeholder to help prepare this ‘magna carta’ on water, its definition of stakeholders mainly involves governments who oblige the bank, private sectors and institutions who have already partnered with the bank’s funds in implementing its activities,” says Roul.