|

Deconstructing Construction in China

This short paper aims to summarise the current condition of China’s construction industry from a labour perspective. The industry has been indispensable to the government’s overall economic strategy over the last 25 years of reform and has played a central role in employment policy, urban housing reform and large-scale infrastructure projects. How the construction industry is managed also has an indirect impact on migration policy, property management, urbanisation, anti-corruption campaigns and even education and medical reforms. Given the centrality of the industry to the economy’s overall health as well as the labour-related issues that the re-structuring of the industry has thrown up, it is surprising how little non-academic attention it has attracted.

This paper will begin with a brief profile of the industry at present and the direction it is likely to go in. A middle section will summarise the workforce and employment structure in the context of the subcontracting system. Unfortunately we do not have space to examine the latter in the detail it deserves. The final section will look at labour relations on site through the prism of a major issue facing workers: wage arrears. Apologies are offered in advance for failing to cover, other than in passing, health and safety issues. Again space precludes an adequate appraisal and while there are obviously specific reasons why China’s construction industry offers the second most dangerous jobs – after mining – the absence of effective and participatory trade union power is at the core of all bad health and safety practice, regardless of industry or sector. We conclude by arguing that there is an urgent need for imaginative policies from the central government. The emergence of a complex system of sub-contracting, the continuing discriminatory environment that building workers find themselves in, and the industry’s poor health and safety performance are just some of the problems demanding powerful trade union action. The government must apply itself to the task of creating the space for construction workers to organise, both in the official trade union and – crucially – beyond it. It is only through genuine and participatory representation that the stability which both the government and construction workers are clearly seeking will emerge.

Current Shape of the Industry

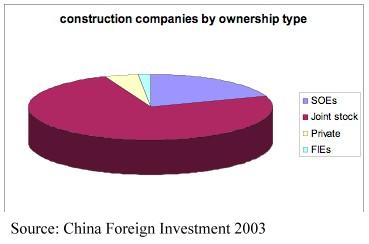

Construction enterprises in China are generally divided into three categories according to their capacity. At the beginning of 2003, there were 65,611 construction enterprises organized along a pyramid structure that generally reflects the shape of the industry in developed countries. Construction companies are graded from ‘A’ to ‘C’ and in 2003, 6 percent were Grade A, 26 per cent were Grade B and the majority, at 65 per cent, was Grade C. The chart below illustrates the types of ownership. The salient features being that there was – and still is – a low level of foreign invested enterprises and that state owned enterprises (SOE) accounted for just fewer than 18 per cent of the total number of enterprises. Pre-WTO restrictions on market access and national treatment account for the former and an early start to privatisation for the latter. Recovery from the post Asian financial crisis (1997-98) has seen a dramatic rise in staff and workers employed by various types of private and semi-private enterprises such as joint ownership, joint stock companies, companies with limited liability as well as foreign enterprises with foreign investment. The numbers working for these enterprises has risen from 330,000 in 1997 to 2.36 million in 2002. Most of them are employed in white collar jobs rather, not the building work itself.

The apparent low density of SOEs needs to be treated with caution. Firstly they are large corporations and their activities in the construction market are disproportionate to their number. Moreover, many joint stock companies are affiliated to construction SOEs for the period of a project and as such have little control over the supply chain. Ongoing research from the Hong Kong-based Asia Monitor Resource Centre points out that SOEs are in a much better position to dominate the market due to access to cheaper land, bank loans, closer connections to the Ministry of Construction (MoC) and the often intimate relationship between senior SOE directors and leading government and Party officials. Given that construction is a traditional site for serious corruption in almost every country, the implications for China are only too clear and have been borne out in practice. Corruption has marred the construction industry at almost every stage of activity: land rights transfers, compulsory land acquisitions, project-related bank loans, demolition and re-housing, materials procurement, quality control, labour relations, health and safety and, of course, remuneration.

In truth, corruption in China’s construction industry is probably no worse than in other countries that have gone through rapid economic transformation and expansion. It is the lack of independent and organised channels of redress that transform the disputes that arise as a result of corruption into profoundly sensitive issues. As part of a response, in early 2005 the Beijing Construction Committee, following patterns already tested in other parts of China, announced that supervision and inspection of construction projects would be assigned to specific and proven management companies with a mandate to supervise not only construction quality but also the time period of a project and the costs incurred throughout the project’s life. The difference between these management companies and the previous inspection organs is that the latter were restricted to monitoring quality control. As we discuss in the section on construction workers, this may possibly ameliorate the problem of wages arrears by bringing more supervision over more of the supply chain, but the fact that the companies are appointed by the developers themselves (jianshe danwei) only further highlights the need for trade union representatives to be involved at all stages of a construction project – including overall management. Both the expanded role for supervisory management companies and the lack of input from trade unions reflect the fact that China’s construction industry is moving closer to the international model.

The construction market in China began to take off in 1992 and by 1996 the industry’s output was five times what it was in the mid-80s. The government designated it a key industry in 1996 and its importance to the overall growth of the economy continues due mainly to a number of interlinked factors: WTO accession in December 2001 and the subsequent increases in the rate of FDI investment; housing and property reforms; the Beijing Olympics in 2008 which includes the construction of 32 stadiums, the Olympic village, and major transport projects; and the Go West policy, which formally started in 1997, and is an attempt by the government to bring development opportunities to central and western China. Combined, these factors will result in a continuation of a steady increase in fixed asset investment and ensure that construction remains a major player. The annual growth rate in 2000 was between 10 and 13 per cent and total output value in the first half of 2005 was up 18.4 per cent on the previous year at over US$150 billion. Profits during the same period continued to grow at an even higher rate of 25.4 per cent on the previous year to US$1.9 billion and are predicted to rise by 30 per cent in 2006. These figures do not include the activities of companies specifically providing labour to the industry; nor do they include the equally impressive statistics from the road and railway infrastructure projects which are accounted for separately.

Page: 1 2 3

|

|